I have to think that the opening sentence of a story or essay is the hardest of all to write. When I taught Freshman Composition, I would remind my students not to get too hung up on their first line. I'd tell them to write something, anything, and just get on with it. One could always come back later. Indeed, later often proved to be the only way to get that first sentence to work--after all the rest of the writing had been done. One finally had context. The ending of things, as it were, provided the beginning.

The same is often true in academic writing when trying to write an introduction. One wants it to be snappy, intriguing: you want it to grab the reader's attention. I was told, and have often read this same advice from others, to leave off writing one's introduction until the end. A Google search on purpose of introduction provides a plethora of advice, most of it rather dry, though all stating pretty much the same thing: "The purpose of the introduction is to orient your reader and create interest in the paper." [Source]

Opening lines in fiction, while sharing the same goal of capturing the reader, require stronger stuff.

"Call me Ishmael" (Herman Melville, Moby Dick, 1851)

”It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.” (Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities, 1859)

"I had the story, bit by bit, from various people, and, as generally happens in such cases, each time it was a different story." (Edith Wharton, Ethan Frome, 1911)

"It was a pleasure to burn." (Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451, 1953)

”We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold.” (Hunter S. Thompson, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, 1971)

Now, after teaching writing for so many years, I find myself in the position of my many students: stuck at the beginning, waiting for that first perfect sentence. In my case, I am trying to use the sentence as a lever; not to open the story--I have the plot well in hand--but to get at the overall approach of the storytelling itself.

Now, after teaching writing for so many years, I find myself in the position of my many students: stuck at the beginning, waiting for that first perfect sentence. In my case, I am trying to use the sentence as a lever; not to open the story--I have the plot well in hand--but to get at the overall approach of the storytelling itself. I am working on a science fiction novel, which may be the issue. The mystery novel I am also working on seems to be able to write itself. The mystery genre has its expected structure and characters. The folks at Scholastic Professional Books have posted a teacher's instructional/help guide, "Genre Characteristics Chart." About the mystery genre it states:

"Usually involves a mysterious death or a crime to be solved. In a closed circle of suspects, each suspect must have a credible motive and a reasonable opportunity for committing the crime. The central character must be a detective who eventually solves the mystery by logical deduction from facts fairly presented to the reader. This classic structure is the basis for hundreds of variations on the form."

My variation has two central character detectives, one a Map Librarian and the other a female Chief of Campus Police. It is an academic mystery. (They say to write what you know and this is so much my world that the world building is a snap though the story itself and the characters and their development are as challenging to write as any other kind of good writing.)

My variation has two central character detectives, one a Map Librarian and the other a female Chief of Campus Police. It is an academic mystery. (They say to write what you know and this is so much my world that the world building is a snap though the story itself and the characters and their development are as challenging to write as any other kind of good writing.)Science fiction writing, for me at least, is a whole other kettle of extraterrestrial fish. As with the mystery, I've already worked out the basic plot. (For the mystery I've actually written the last scene of the fifth and final book of the series which is rather cheeky of me since Book 1 has yet to be written!) But really good SF wants new worlds and, to my mind, something a little more in the presentation.

Sheri S. Tepper (1929-2016) had the knack of dropping her readers in the middle of it all. You are forced to sort things out as you go. After Long Silence and Grass are good examples of this. The settings are just familiar enough to lull you into thinking you know where she is headed but the setting shifts and the plot refuses to play along with your expectations.

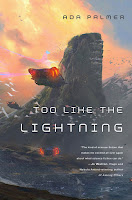

Ada Palmer's Terra Ignota series grabs you by the scruff of your readerly neck and pulls you along rather whether you like it or not! Her setting is our own Earth but, while the geography and language are all familiar, her future history is a splendid, mind-breaking (in my case) assault on what our current history transformed into.

I confess I am still working my way through these, struggling really (and she is still writing the final novel of the set). As an aspiring SF writer I find her description of herself and her approach profoundly useful, however. Here's what Palmer says of herself on the About page from her website: "All my projects stem from my overall interest in the relationship between ideas and historical change. Our fundamental convictions about what is true evolve over time, so different human peoples in different times and places have, from their own perspectives, lived in radically different worlds with radically different rules."

That kind of rigorous grasp of vision is what I am aiming for--and is why I am struggling with how to approach the opening of my novel. Is it a straight out chronological narrative? A collection of miscellaneous science reports, character letters and/or journal entries, and vignettes a la Le Guin's Always Coming Home?

No answers to report just yet. For now I am simply grabbing various books off my shelves and reading the first few pages just to see how various writers are doing things:

"The Western plains of New South Wales are grasslands. Their vast expance flows for many hundreds of miles beyond the Lachlan and Murrumbidgee rivers until the desert takes over and sweeps inland to the dead heart of the continent." (Jill Ker Conway, The Road from Coorain, 1989).

"How the patient scientist feels when the shapeless tussocks and vague ditches under the thistles and scrub begin to take shape and come clear: this was the outer rampart--this the gateway--that was the granary! We'll dig here, and here, and after that I want to look at that lumpy bit on the slope. . . ." (Ursula K. Le Guin, Always Coming Home, 1985)

"This is written from memory, unfortunately. If I could have brought with me the material I so carefully prepared, this would be a very different story. Whole books full of notes, carefully copied records, firsthand descriptions, and the pictures--that's the worse loss. We had some bird's-eyes of the cites and parks; a lot of lovely views of streets, of buildings, outside and in, and some of those gorgeous gardens, and, most important of all, of the women themselves." (Charlotte Perkins Gillman, Herland, 1915)

Right now, landscapes seem to be what I need. I'll see where this takes me!

_____________________________________________________

* For more on Palmer's approach, see this panel discussion transcript: "Fiction and History: Narratives, Contexts and Imagination", by Ada Palmer, Jane Dailey, Ghenwa Hayek, Paola Iovene, David Perry. Chicago Journal of History, Spring 2017

Image Credits/Links (all images either public domain or Creative Commons CC0):

- Once upon a time writing

- Black man reading a book

- An illustration from Herman Melville's Moby-Dick

- Fountain pen on handwritten letter

- Woman detective

- Africa - Namibia Landscape

Book cover images from Amazon or Goodreads.